Imagine driving past Columbus Middle School and seeing former Dodger Shawn Green catch fly balls in right field.

Or maybe Currie Middle School and seeing Tim Wallach, a former Montreal Expos and Dodgers star, picking up a grounder at third base.

Or some other college, minor league or major league star who once called Tustin home, and played on the fields at those schools and others in town – Utt, Currie, the Tustin Pony League field on Red Hill, and the baseball diamonds at Tustin and Foothill high schools.

Those fields and more have been home to hundreds of thousands of youngsters who have played playground or organized baseball in the city since it was incorporated in 1927. In 1960, the city had four Little League organizations playing at four middle schools.

Green (Tustin High), Wallach (University) and Mark Grace (Tustin) are three of the 10 players from town who reached the major leagues, between them playing more than 50 years and reaching star status in the game before retirement. Green set the Dodger single-season record for home runs, Wallach was a star in Montreal and is a Dodgers coach, and Grace was probably the most beloved member of the Chicago Cubs during his 13 seasons there.

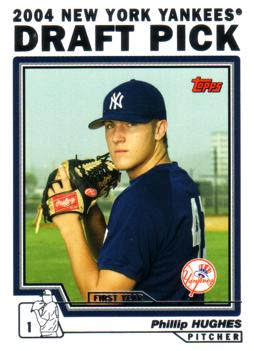

There are four players in the majors today from Tustin – Phil Hughes (Foothill), Brad Boxberger (Foothill), Heath Bell (Tustin) and Gerrit Cole (Orange Lutheran). All are pitchers and three of them are former first-round draft picks.

“This has always been a baseball town,” Vince Brown said, and he would certainly know. Brown was the baseball coach at Tustin from 1986 to 1992, and has served in a variety of jobs at Foothill since 1995 – baseball coach, assistant coach and athletic director.

“The baseball dynamic here has always been great. The youth programs have been feeder programs for Tustin high schools and other high schools nearby. There were kids who were clearly headed for success and kids who weren’t on anyone’s radar at the time.

“They had the opportunity to play in quality programs that prepared them for baseball and for life. You have to be very fortunate to get to the highest level.”

The 10 players whose paths began in Tustin took different routes to the major leagues.

Wallach blossomed in college. Grace was a low-round draft pick out of college who became an icon with the Cubs. Bell was undrafted and spent six years in the minors before becoming one of baseball’s best closers with the San Diego Padres.

Green and Cole had success in local youth leagues before becoming first-round draft picks out of high school. Hughes matured while in high school, also en route to becoming a first-round draft picks.

Green’s family moved from San Jose to Tustin when he was 12, and he was an immediate standout for Tustin Western Little League, helping the 12-year-old all-stars reach the sectional title game. He excelled in Tustin Pony League after Little League.

“It was a good baseball town with good coaches,” said Green, now an entrepreneur living in Newport Beach. “Tim O’Donoghue was my Little League coach, and he made sure we had fun while learning the game. For someone who dreamed of reaching the major leagues, it was a great start.

“You learn a lot more as you grow. Vince was a great high school coach. What I remember most is how much baseball talent there was in the city – it helps so much to be around good players – and how supportive parents were. There were so many teammates (in youth ball) who went on to play in college or professionally.”

“Shawn was a great youth player and came into high school with a lot of expectations,” Brown said. “He was the only player I ever had who was on the varsity for four years. By the time he was a senior he was still kind of a skinny kid, but he could put the bat on the ball. I knew he would have the opportunity to grow into a great player and man.”

Wallach played at Tustin National Little League at Currie Middle School then advanced to Pony and Colt baseball.

“That was back when kids played all sports,” Wallach, now the Dodgers bench coach, said. “We played baseball for four months and then moved on.

“What I remember most was going to the field and spending the whole day there, either playing or watching other games. I don’t remember anything negative about my youth baseball experience, which may have been the best thing of all. We played ball and had fun. They didn’t make it bigger than it should have been.”

Wallach lived in Tustin but went to just-opened University High in Irvine.

“We didn’t have a lot of success, but I had a good coach in Ken Trotter,” he said. Wallach was honored as a distinguished alumnus at a gala in 2012.

Wallach was a solid player, but he was undrafted out of high school and remained undrafted after two years at Saddleback College. His career took off when he went to Cal State Fullerton in 1978. By the time he finished his 1979 senior season with a College World Series title and a slew of school records, he jumped to the 10th pick overall in the 1979 draft.

“I learned a lot from coaches Dick Stuetz and Jim Brideweser at Saddleback,” he said. “But Fullerton is where I grew up. Augie Garrido took me from being a good player to being someone who was drafted.”

Grace and his family didn’t move to Tustin until he was in the eighth grade but was impressed by the level of baseball being played at area high schools.

“I was coming from Tennessee to a place where baseball could be a year-round sport because of the climate,” he said. “And once I was on a team, I realized how good the level of baseball was here than most other cities. I was probably the third- or fourth-best player on my team. It was just better baseball.

“There were so many great programs nearby – Santa Ana, Orange, El Modena, Villa Park. The old Century League was full of big schools with big players. We’d go play in these Easter Tournaments and there was just so much baseball talent on those fields.”

Brown says the legacy for Tustin baseball is that everyone has stayed close to the city.

“I didn’t know Mark Grace well. He played before I got here,” Brown said. “But I had a chance to meet him years later at a Dodgers game. When Shawn signed with Toronto, he made a donation to the high school program. A few days later, Mark called to match the donation.”

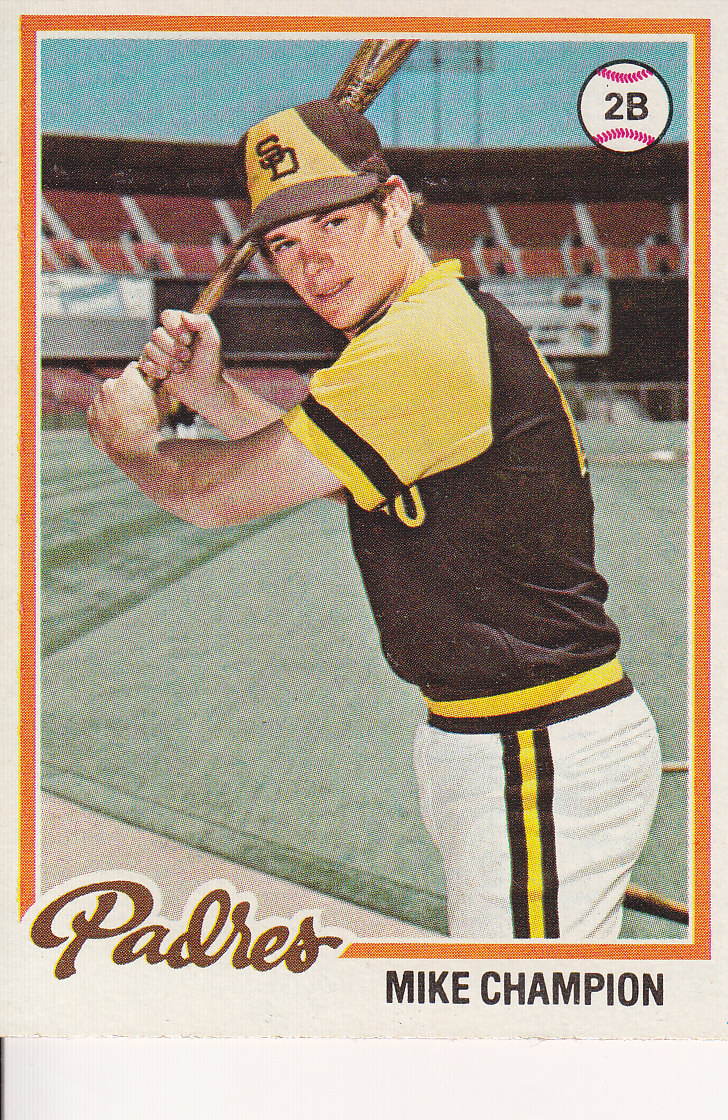

Mike Champion was the first area player to reach the majors, in 1976 with the Padres, and years later Brown coached his son Skylar at Foothill. He also coached Mike Schwabe, who would go on to set pitching records at Santa Ana College and was an All-American at Arizona State. Schwabe is now a coach at Tustin’s baseball clinic.

Brown was athletic director at Foothill when Brad Boxberger led the Knights to a CIF title in 2006 and watched Phil Hughes’ development.

“Neither Brad nor Phil were acclaimed players when they got to high school, but they had high expectations of themselves,” Brown said. “Brad’s dad Rod pitched at Foothill and USC, so the family is attached the city. Brad came in with the desire to be as good as his dad.”

Brown laments that Cole never went to Foothill. Cole led the 2003 Tustin Western Little League deep into the all-star playoffs, as well as a Tustin Pony team a year later. His family chose to send him to Orange Lutheran High, where he earned CIF honors and was named to USA Today’s All-USA team. He was a first-round pick by the Yankees in 2008, but spurned them to play college baseball at UCLA. He was the first pick in the 2011 by the Pirates and already is the team ace.

Brown saw Hughes develop virtually overnight. He made a few appearances with the Foothill varsity as a sophomore. “By his junior year, I was talking with his parents about preparing for his being a first-round pick,” Brown said.

“Phil was driven with a passion to be a success. Every kid is different; they all mature at different times. But what I’ve seen often over the years is so many kids with the desire to be a success, no matter where in baseball they wound up.’’

THE PLAYERS

DAVE STATON, Tustin High School

Staton was a power hitter who had a .575 batting average with eight home runs as a senior in 1985. He played two seasons at Orange Coast College, and in 1988 he had a memorable summer with Brewster in the prestigious Cape Cod League, hitting .359 with 16 home runs. He's a member of the league's Hall of Fame.

He then had a blistering season at Cal State Fullerton in 1989, hitting .371 with 18 home runs and 77 RBI, the latter mark breaking Tim Wallach's single-season school record. Staton, who struggled with lupus as a teen and had to sign a medical waiver to play baseball, was a fifth-round pick by San Diego in 1989.

He then had a blistering season at Cal State Fullerton in 1989, hitting .371 with 18 home runs and 77 RBI, the latter mark breaking Tim Wallach's single-season school record. Staton, who struggled with lupus as a teen and had to sign a medical waiver to play baseball, was a fifth-round pick by San Diego in 1989.He won the triple crown in his first pro season for Spokane in the Northwest League (.362 average, 17 home runs, 72 RBI). He hit 103 home runs in the minors from 1989 to 1993. He got two trials with the Padres in 1993 and 1994, hitting nine home runs in 108 at-bats.

He was signed by the Dodgers for 1995 but declined to play for the major league team as a replacement player during the 1994 players strike. He spent one more season in the minors before retiring. He now coaches hitting at a baseball academy in Tustin.

BRAD BOXBERGER, Foothill High School

The right-handed pitcher was the CIF-Southern Section Division 2 player of the year as a senior at Foothill, going 12-0 with a 1.17 ERA and leading the Knights to the division title with a 4-3 extra-inning win over St. Francis. He was a three-year starter at USC, with 11 career wins and a 3.20 ERA as a freshman and 3.16 as a junior.

He was a 2009 first-round pick by Cincinnati (43rd player overall). He was traded to San Diego and made his major league debut in 2012, posting a 2.60 ERA in 24 relief appearances. After another year with the Padres, he was traded to Tampa in 2014 and had a breakout season, going 5-2 with a 2.37 ERA and 104 strikeouts in 63 appearances out of the bullpen.

MIKE CHAMPION, Foothill High

Champion was the first Tustin player to reach the major leagues. A shortstop, he was a second-round pick in the 1973 draft by San Diego, and spent three seasons with the Padres. In 1977, he was the starting second baseman, playing in 150 games with 12 doubles and 43 RBI with a .229 average.

Champion was the first Tustin player to reach the major leagues. A shortstop, he was a second-round pick in the 1973 draft by San Diego, and spent three seasons with the Padres. In 1977, he was the starting second baseman, playing in 150 games with 12 doubles and 43 RBI with a .229 average.Champion's son Skylar was also a star athlete at Foothill.

MIKE SCHWABE, Tustin High

The 6-foot-4 right-hander was a star at Tustin whose career took off at Santa Ana College, where he won 25 games in two seasons, the record for most career wins. He was 13-2 with a 1.16 ERA in 1985. He transferred to Arizona State and went 12-6 with a 3.02 ERA to earn all-Pac 10 honors and help the Sun Devils to the 1987 College World Series.

The 6-foot-4 right-hander was a star at Tustin whose career took off at Santa Ana College, where he won 25 games in two seasons, the record for most career wins. He was 13-2 with a 1.16 ERA in 1985. He transferred to Arizona State and went 12-6 with a 3.02 ERA to earn all-Pac 10 honors and help the Sun Devils to the 1987 College World Series.Detroit drafted him in the 21st round of the 1987 draft and he made his debut in 1989, throwing five-plus innings to get the win in his first start. He made 13 appearances in 1989 and one in 1990 for the Tigers. He spent a few more years in the minors before starting a coaching career. He is the pitching coach for GWE Baseball in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

HEATH BELL, Tustin High

A standout Tiller, Bell's major league career took awhile to take off. After two years at Rancho Santiago College, he signed as a free agent with the New York Mets in 1998 and spent six years in the club's farm system before a trade to San Diego.

He had five strong seasons with the Padres, posting 40-plus saves each year from 2009-11 and was named to three all-star teams. He pitched for Miami in 2012, Arizona in 2013 and Tampa in 2014, and has signed a contract with the Washington Nationals this year.

Cole grew up in Tustin and was on the 2003 Tustin Western Little League all-star team that reached the regional finals and won a Pony League championship a year later. He was an All-CIF pitcher at Orange Lutheran and a USA Today All-USA pick after the season. He was drafted by the Yankees after his senior season in 2008, but chose not to sign and played three years at UCLA. In 2011, he was the first pick in the amateur draft and has already become the Pittsburgh Pirates' ace. In two seasons, he has a 21-12 record and 3.45 ERA in 41 major league starts.

MARK GRACE, Tustin High

In his 16-year career, 13 with the Cubs, Grace hit for a .303 average, had 511 doubles, 173 home runs and drove in 1,146 runs. In 1989, he was 11 for 17 in the National League championship series against San Francisco, the Cubs just missing their first World Series appearance since 1945.

He finished his career with Arizona, hitting .298 with 16 home runs in 2001 and helping the Diamondbacks to the World Series over the New York Yankees. He started the D-backs' pivotal Game 7 two-run, ninth-inning rally with a single. He was a broadcaster for the club for nine years and is now a hitting coach.

SHAWN GREEN, Tustin High

Green was an All-CIF player at Tustin, where he led the Tillers to the 1991 CIF-SS 3A title game. He was a 1991 first-round pick (16th overall) by Toronto and had a breakout season in 1999 with 42 home runs. He was traded to the hometown Dodgers after the season and had three seasons with 40-plus home runs, including a club record with 49 in 2001. He shares the major league record for most home runs in a game (four).

He had a five-year career with the Dodgers and also played with Arizona and the New York Mets before retiring. In 15 seasons, he hit 445 doubles, 328 home runs, drove in 1,070 runs and stole 162 bases. He finished in the top 10 in MVP voting in 1999, 2001 and 2002 and was a two-time All-Star.

Green does community service work with the Dodgers and is an entrepreneur living in Newport Beach with his family. He wrote a 2011 book on his baseball career and his philosophy toward the game, "The Way of the Baseball: Finding Stillness at 95 mph."

PHIL HUGHES, Foothill High

Hughes developed tremendously during his career at Foothill High, by his senior season in 2004 becoming one of the top prospects in the nation. He was a 2004 first round draft pick by the Yankees (23rd overall).

He made his major league debut in 2007 and has posted a 72-60 career record in eight seasons. He spent seven with the Yankees, going 18-8 with a 4.19 ERA to earn an all-star spot in 2010 and was 16-13 in 2012, also with a 4.19 ERA. He signed with Minnesota as a free agent in 2014 and was the Twins' ace, going 16-10 with a 3.52 ERA and career highs of 186 strikeouts in 209-plus innings.

TIM WALLACH, University High

Wallach grew up in Tustin but was assigned to the new University High in Irvine because he lived near its border. A standout there, he was undrafted out of high school and played two seasons at Saddleback College before transferring to Cal State Fullerton.

He blossomed with the Titans. In 1978, he hit .394 with 16 home runs and 80 RBI, all school records; in 1979, he hit .293 with 20 home runs and 102 RBI while leading the Titans to a 60-14-1 record and first College World Series title. He was inducted into the College Baseball Hall of Fame in 2011.

He blossomed with the Titans. In 1978, he hit .394 with 16 home runs and 80 RBI, all school records; in 1979, he hit .293 with 20 home runs and 102 RBI while leading the Titans to a 60-14-1 record and first College World Series title. He was inducted into the College Baseball Hall of Fame in 2011.He was Montreal's first-round pick in the 1979 draft (10th player overall) and he made his major league debut in 1980, the first of 17 seasons in the majors. He played 13 seasons for the Expos, four with the Dodgers and part of one season with the Angels. He was a five-time all-star, won three Gold Gloves at third base, finished fourth in MVP voting in 1987, and ended his playing career with 432 doubles, 260 home runs, 1,125 RBI and a .257 average.

Wallach immediately went into coaching and managing on the minor league level, starting in the Dodgers system and moving up to be manager of their Albuquerque AAA team before joining the Dodgers' coaching staff as third-base coach in 2011.

Source: http://www.ocregister.com/articles/baseball-651781-tustin-high.html?page=1